Why Do People Continue to Have Children in Countries There is Not Enough Food

Being hungry means more than just missing a meal. It's a debilitating crisis that has more than 820 million people in its grip, with millions more now under its threat due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

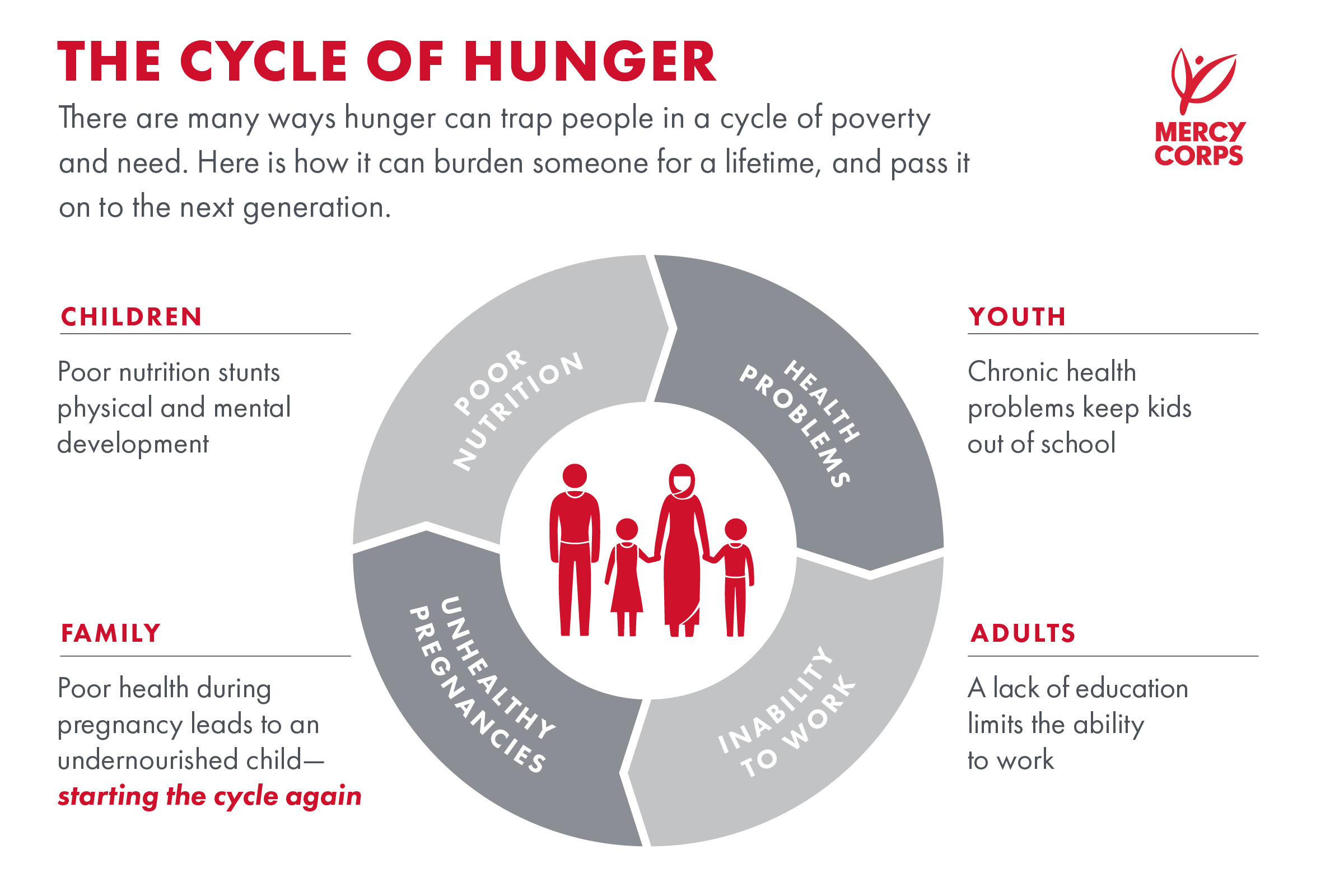

Hunger is a perilous cycle that passes from one generation to the next: Families who struggle with chronic hunger and malnutrition consistently go without the nutrients their minds and bodies need, which then prevents them from being able to perform their best at work, school, or to improve their lives.

Mercy Corps believes that breaking the cycle of poverty and building strong communities begins when every person has enough nutritious food to live a healthy and productive life. It is key to our work in more than 40 countries around the world.

Read on to learn more about the global hunger crisis, including the potentially devastating effects caused by COVID-19.

- Who is hungry?

- Why are people hungry?

- How does hunger affect people's lives?

- What effect is COVID-19 having on the global hunger crisis?

- How is Mercy Corps addressing the hunger crisis?

Who is hungry?

Around the world, 821 million people do not have enough of the food they need to live an active, healthy life. One in every nine people goes to bed hungry each night, including 20 million people currently at risk of famine in South Sudan, Somalia, Yemen and Nigeria.

People suffering from chronic hunger are plagued with recurring illnesses, developmental disabilities and low productivity. They are often forced to use all their limited physical and financial resources just to put food on the table.

Hunger in the developing world

Ninety-eight percent of the world's hungry live in developing regions. The highest number of malnourished people, 520 million, lives in Asia and the Pacific, in countries like Indonesia and the Philippines.

In sub-Saharan Africa, 243 million people face hunger in arid countries like Ethiopia, Niger and Mali.

And millions of people in Latin America and the Caribbean are struggling to find enough to eat, in places like Guatemala and Haiti.

The majority of these hungry families live in rural areas where they widely depend on agriculture to survive.

Hunger for women and girls

In many places, male-dominated social structures limit the resources women have like job opportunities, financial services, and education, making them more vulnerable to poverty and hunger.Sixty percent of the world's hungry are women and girls.

This, in turn, impacts their children. A mother who suffers from hunger and malnourishment has an increased risk of complications during childbirth or delivering an underweight baby, which can mean irreversible physical and mental stunting right from childbirth. Learn more about the impact of malnutrition ▸

Why are people hungry?

Drought

As a result of climate change and increasingly unpredictable rainfall — has become one of the most common causes of food shortages in the world. It consistently causes crop failures, kills entire herds of livestock, and dries up farmland in poor communities that have no other means to survive.

Food is inaccessible

Many hungry people live in countries with food surpluses, not food shortages. The issue, largely, is that the people who need food the most simply don't have steady access to it.

In the hungriest countries, families struggle to get the food they need because of several issues: lack of infrastructure, frequent war and displacement, natural disaster, climate change, chronic poverty and lack of purchasing power.

The majority of those who are hungry live in countries experiencing ongoing conflict and violence — 489 million of 821 million. The numbers are even more striking for children. More than 75 percent of the world's malnourished children (122 million of 155 million) live in countries affected by conflict.

Get the facts about the food crisis in war-wracked South Sudan ▸

Food is wasted

Up to one-third of the food produced around the world is never consumed. Some of the factors responsible for food losses include inefficient farming techniques, lack of post-harvest storage and management resources, and broken or inefficient supply chains.

How does hunger affect people's lives?

Hunger traps people in poverty

People living in poverty — less than $1.25 USD per day — struggle to afford safe, nutritious food to feed themselves and their families. As they grow hungrier they become weak, prone to illness and less productive, making it difficult to work. If they're farmers, they can't afford the tools, seeds and fertilizer they need to increase their production, let alone have the strength to perform laborious work.

The limited income also means they often can't afford to send their children to school or they pull them out to work to help support the family. Even if children are lucky enough to go to class, their malnourishment prevents them from learning to their fullest.

Lack of education prevents better job opportunities in the future, confining yet another generation to the same life of poverty and hunger.

Hunger stunts futures

Children around the world are undernourished, and most of them are suffering from long-term malnourishment that has serious health implications that will keep them from reaching their full potential.

Malnutrition causes stunting — when the body fails to fully develop physically and mentally — and increases a child's risk of death and lifelong illness. A child who is chronically hungry cannot grow or learn to their full ability. In short, it steals away their future.

Hunger kills

Hunger and malnutrition are the biggest risks to health worldwide - greater than AIDS, malaria and tuberculosis combined. Undernutrition is the cause of around 45% of deaths among children under five. Children who live in extreme poverty in low income countries, especially in remote areas, are more likely to be underfed and malnourished.

Globally, food deprivation still claims a child's life every three seconds and nearly half of all deaths in children under 5 are attributable to undernutrition.

Read about how hunger is threatening nearly 18 million lives in Yemen ▸

What effect is COVID-19 having on the global hunger crisis?

As Coronavirus, or COVID-19, continues to spread around the world, it is now reaching countries most vulnerable to the health and economic impact of the virus. People fleeing conflict, living in poverty or without access to healthcare face greater risk from this pandemic.

Food cannot get to those who need it and 130 million more people could go hungry in 2020. Over 368 million children are missing meals and snacks because schools have been shut down. Restrictions on movement are already devastating the incomes of displaced people in Uganda and Ethiopia, the delivery of seeds and farming tools in South Sudan, and the distribution of food aid in the Central African Republic. Altogether, an estimated 265 million people could be pushed to the brink of starvation by the end of 2020.

Countries that depend on imported food are especially vulnerable to slowing trade volumes, especially if their currencies decline. While retail food prices are likely to rise everywhere, the impact is more severe when the change is sudden, extreme and volatile, particularly in places where food costs account for a larger share of household budgets.

The most devastating effects in Africa will be felt by those already most vulnerable - people and communities in fragile or conflict-affected places, especially internally displaced people and refugees, with weak health systems, struggling economies, and poor governance.

The World Bank projects that economic growth in Sub-Saharan Africa will decline from 2.4 percent in 2019 to -2.1 to -5.1 percent in 2020, the first recession in the region in 25 years. That will result in 80 million more people across the continent living in extreme poverty. This is a significant setback, given that March 2019 was the first time in recent history that more Africans were escaping extreme poverty than being born below the poverty line.

The United Nations Development Program estimates that developing countries stand to lose $220 billion in income, and that half of jobs across Africa could be lost due to the pandemic.

The locust outbreak

Adding even greater urgency to the situation, a plague of desert locusts -- the most devastating migratory pest in the world -- began to descend on countries in the Horn of Africa and East Africa in the middle of last year. Measures intended to prevent the spread of the novel coronavirus pandemic are unwittingly slowing the essential response to prevent these pests from wiping out food supplies.

After the eggs hatch in May, we anticipate new swarms will form in June and July, which will coincide with the start of the harvest season. This could not be worse timing. An adult locust can consume roughly its own weight in fresh food per day, which is about two grams every day. An average swarm can destroy crops sufficient to feed 2,500 people for a year. There can be 40 million and sometimes as many as 80 million locust adults in each square kilometer of swarm.

The confluence of the locust and COVID-19 crises poses an unprecedented threat to the food security and livelihoods of millions of people. At a time when the UN is estimating that the number of people suffering from hunger could go from 135 million to more than 250 million in the next few months, many of these are likely to be in east Africa.

We are facing a catastrophe. Due to the nature of the global COVID-19 pandemic, it is recognized that many countries also need to look inwards. Still, the most vulnerable people and communities continue to need our support, now more than ever.

Our response to COVID-19

In response to the crisis, Mercy Corps is expanding upon a strong foundation of success fighting Ebola to provide critical support to vulnerable communities across the world. We are focusing efforts on protecting health, which includes public outreach, clean water and sanitation services. Our teams are on the front lines, meeting immediate needs such as cash distributions to provide families with food, soap and health care. And we're working to sustain and strengthen economies by supporting smallholder farmers and small businesses through this crisis.

How is Mercy Corps addressing the hunger crisis?

Boost production

The world's population is projected to rise to around 10 billion by 2050 — up from more than 7 billion today. That meansthere will be over 2 billion more people who need food by 2050. Making sure there's enough for everyone to eat will be an increasing concern as the population multiplies.

Even though we must increase production by 50 percent to keep up with the demand and find new, secure sources of food, the main challenge in the future fight against hunger will be the same one we're facing today: ensuring that every family is able to access it.

Increase access

There is 17 percent more food available per person than there was 30 years ago. And if all the world's food were evenly distributed, there would be enough for everyone to get 2,700 calories per day — even more than the minimum 2,100 requirement for proper health. The challenge is not a lack of food — it's making food consistently available to everyone who needs it.

Empower women

Supporting women is essential to global food security. Almost half of the world's farmers are women, but they lack the same tools — land rights, financing, training — that their male counterparts have, and their farms are less productive as a result.

If women and men had equal agricultural resources,female farmers could lift as many as 150 million people out of hunger.

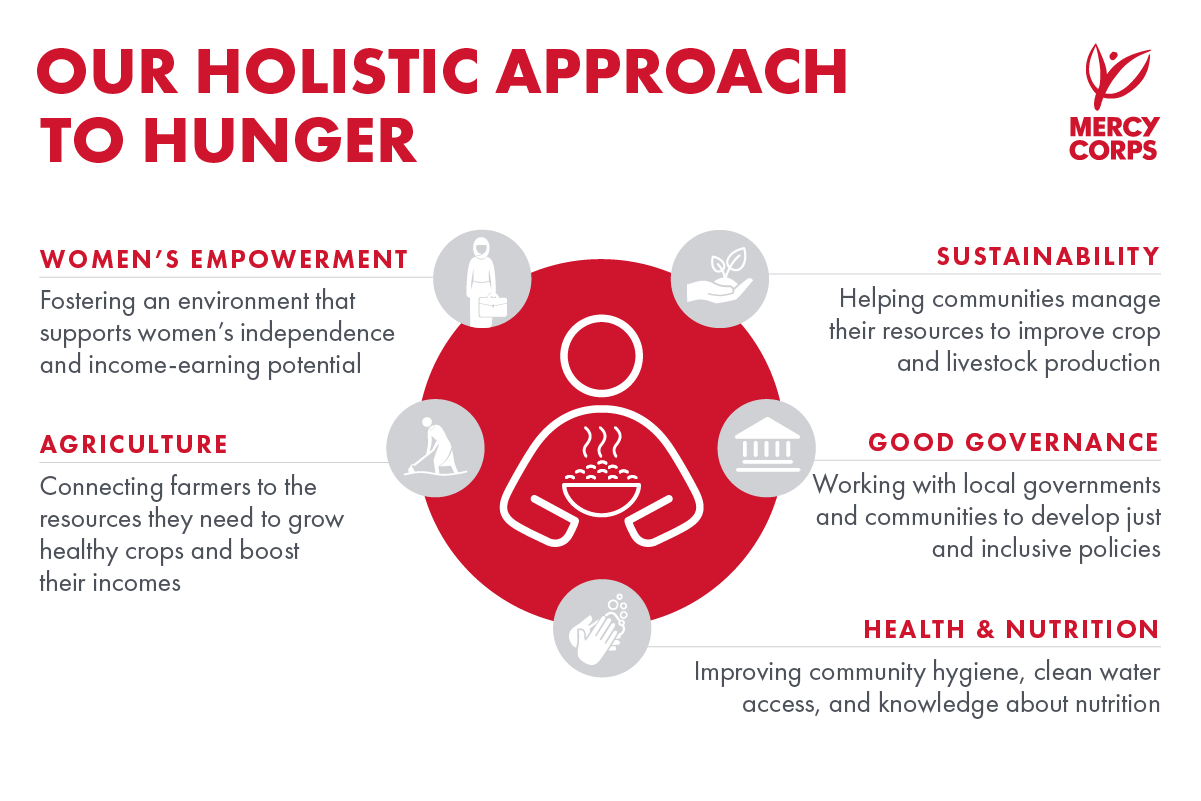

Our holistic approach to hunger

Mercy Corps takes a holistic approach to alleviate hunger and help communities meet their own food needs far into the future.

We respond to urgent needs: When disaster, war or a pandemic like COVID-19 creates a hunger crisis, we quickly provide emergency food, cash or vouchers to buy food, treatment for malnutrition, and short-term employment so people can earn the money to buy food locally.

We support overall health: We teach nutrition and hygiene, help new mothers properly care for infant and child needs, and improve access to clean drinking water and sanitation, so people can avoid disease and benefit fully from the food they eat.

We build a more food-secure future: We connect buyers and sellers to increase farmers' incomes and strengthen markets, introduce mobile financial services to help farmers grow their business, and teach communities to protect and preserve the environment they depend on.

We must continue to act.

The number of people living with hunger appears to be on the rise. About 2 billion people have been freed from hunger since 1990, when the United Nations set the development goal to halve the number of people suffering from hunger by 2015. In 2019, the United Nations reported that after nearly ten years of progress, the past three years have seen an increase in the number of people suffering from hunger. Now, with the COVID-19 pandemic before us, the global hunger crisis stands to grow and threaten the lives of more vulnerable communities across the world. Please join us on our mission and help us provide critical support to those who need it most.

Source: https://www.mercycorps.org/blog/quick-facts-global-hunger

0 Response to "Why Do People Continue to Have Children in Countries There is Not Enough Food"

Post a Comment